As we approach the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of the Second World War, it’s worth remembering that many of the countries caught up in it were unwilling participants. Rather than enlisting in a universal crusade against the evils of Nazi Germany, they wanted nothing more than to stay out of the conflict.

As we approach the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of the Second World War, it’s worth remembering that many of the countries caught up in it were unwilling participants. Rather than enlisting in a universal crusade against the evils of Nazi Germany, they wanted nothing more than to stay out of the conflict.

For instance, the likes of Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway didn’t declare war in response to the German invasion of Poland. They got involved because they, too, were subsequently invaded.

Similarly, the United States stayed out until it was attacked in 1941. And the Soviet Union began the war as Adolf Hitler’s collaborator in the carve-up of Poland, only becoming a mortal enemy when Hitler turned on it.

In Europe, only five states successfully maintained their neutrality throughout – the Iberian dictatorships of Spain and Portugal, and the democracies of Sweden, Switzerland and Ireland.

And being neutral could be an ambivalent business. Both Sweden and Switzerland maintained close economic ties with their German neighbour, so much so that they’ve been retrospectively criticized for aiding and abetting the German war effort.

Ireland’s situation was different.

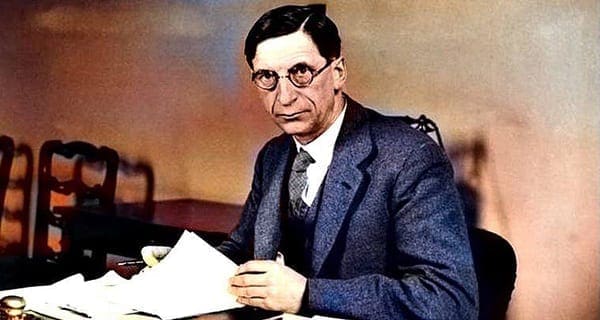

Traditionally, Irish Prime Minister Eamon de Valera is perceived as the man who kept Ireland out of the war. And that was certainly his objective, to which he devoted his considerable political and diplomatic talents.

But de Valera biographer David McCullagh offers up another candidate: British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 left three Irish ports in British military hands. Strategically, they had value as a means of extending protection for transatlantic shipping, a consideration that would assume particular importance in the event of a war with Germany. Preserving that maritime lifeline would be critical.

Nonetheless, and without any prior agreement to allow Britain to use them in the event of war, Chamberlain transferred the ports to Irish control in 1938. And when war did break out, Ireland refused permission for such use.

Had the ports still been in British hands, they’d have been natural targets for German bombing. They might well have been the catalyst for triggering execution of the German Seventh Army’s provisional 1940 plan for an invasion targeted at Ireland’s southeast coast.

Chamberlain, however, had decided that surrendering the ports unconditionally was a price worth paying for what he hoped would be Irish goodwill. It was of a piece with his general approach of seeking to remove causes of friction between states. Whether this qualified as appeasement or merely a plausible policy that didn’t pan out is a matter of historical interpretation.

Irish neutrality differed from that of Sweden and Switzerland in several respects.

First, as Germany’s neighbours and trading partners, Sweden and Switzerland had to reckon with the fact that it was a large and immediate presence, one they couldn’t wish away. Ireland didn’t have the same circumstances to deal with as far as Germany was concerned.

Second, whereas the Swedes and the Swiss pursued a policy of armed neutrality by building up their military forces, Ireland’s self-defence effort was especially weak. Entering the war years with a very small army, virtually no aerial capability and little by way of a naval service, Ireland was a sitting duck for any serious big power invader.

And third, although scrupulously even-handed with respect to the formalities, de Valera positioned Ireland so that it was – in historian Joseph Lee’s terms – “benevolently neutral for Britain.” Sweden, in contrast, has been described as “an extension of Germany’s war industry” up until at least 1943.

This “benevolence” took a number of forms.

There was intelligence co-operation with Britain’s MI5, plus a tacit understanding that the British would pursue German submarines in Irish territorial waters. Irish food exports to Britain were also important.

And Dublin did nothing to impede the tens of thousands of Irishmen who volunteered to serve in the British forces. In addition, over 100,000 Irish people crossed the Irish Sea to work, helping to alleviate Britain’s wartime manpower shortage (while simultaneously reducing Ireland’s unemployment rate and generating a flood of financial remittances).

When it was over and the full horrors of Nazi Germany became undeniable, neutrality acquired something of a retrospective moral taint. Nobility isn’t hard when it’s after the fact.

In reality, though, staying out of the war was what most countries aspired to.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.